When AI gets on your nerves

Physiologists at FAU use neural networks to analyze the function of ion channels

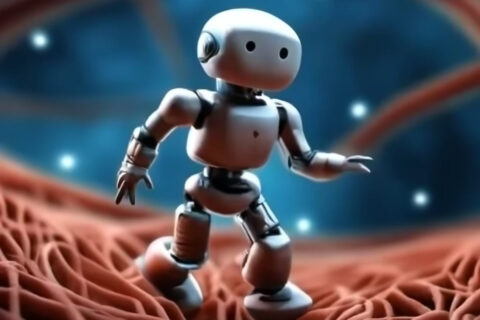

Deep neural networks will allow signal transfer of nerve cells to be analyzed in real time in future. That is the result of a study conducted by physiologists at Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) that has been published in the journal Communications Chemistry. The method is not only of relevance for neuromedicine, it can also be used for investigating chemical reactions.

Nerve cells are the information carriers in our brain. When transferring signals they change their electrical charge by regulating the concentration of sodium or potassium ions via ion channels. These channels are located in the cell membrane and work like electrical switches. “There is an established method that can be used to measure whether an ion channel is open or closed,” explains PD Dr. Dr. Tobias Huth from the Institute of Physiology and Pathophysiology at FAU. “This involves placing an extremely fine pipette of just one micrometer in diameter at the channel and recording changes in electrical current.” The problem with this patch-clamp technique is that numerous disruptive factors in the surrounding environment make it difficult to detect the extremely weak currents the ion channels work with. Low-pass filters minimize noise, but restrict the bandwidth for measurements. “Our experiments result in a condensed time series recording of the electrical currents that resembles a never-ending barcode,” explains Efthymios Oikonomou, doctoral candidate at the Institute of Physiology and Pathophysiology and main author of the study. “Evaluating these single channel datasets is extremely time-consuming and requires enormous computing power.”

The researchers from Erlangen have now presented a method aimed at considerably increasing the speed of analysis using deep neural networks. The first step involves transforming the time series recordings into two-dimensional histograms. These compact graphs that can be compared to QR codes eliminate superfluous information and present all the essential data in a very small space. “We simulated millions of these histograms on a mainframe for training the AI. If we had restricted ourselves to only using genuine measurements, it would have taken decades,” Oikonomou explains.

The trained neural networks are in a position to analyze unknown electrical currents with lightning speed, thereby observing how ion channels work in real time. “This opens the door to previously unheard of opportunities for investigating brain function including neural disorders and diseases,” explains Tobias Huth. “For example, it is possible for us to track how nerve cells react to new medicines in virtually real time.” Using deep neural networks to process histograms is not only of interest for medical applications, however. The method may also prove beneficial for any instances where there is a requirement to describe changes of state that are rapid and difficult to predict, for example in the case of chemical reactions.

Efthymios Oikonomou and PD Dr. Tobias Huth are both involved in the Alzheimer/Huth working group at the Institute of Physiology and Pathophysiology. Their focus lies on the electrical behavior of neurons and neural networks in the central nervous system under normal and pathological conditions. They use high resolution neurophysiological and optical methods to investigate the functions and regulation of ion channels and synapses.

Further information:

PD Dr. Dr. Tobias Huth

Institute of Physiology and Pathophysiology

tobias.huth@fau.de